For many diaspora communities, musical expressions can be one of the artifacts that captures change, influences, innovations, or even the possibility of remaining static. What happens to these musical expressions over time and through generations, is exemplified by the klezmer musicians of Veretski Pass who, as American Jews of Eastern European descent, have been crucial to the revival of this genre and have added to the klezmer repertoire with thorough research and much heart.

Veretski Pass artists, Cookie Segelstein, Joshua Horowitz and Stuart Brotman have over 40 recordings under their belt focusing on instrumental Jewish music from Eastern Europe. The name of the trio refers to a pass through the Carpathian Mountains located near the western border of Ukraine, at the base of which Cookie’s father was born. Their focus is on Jewish, instrumental music from Eastern Europe prior to the Second World War. As Cookie once told an audience, “This is not your grandmother’s klezmer. It is her grandmother’s klezmer.”

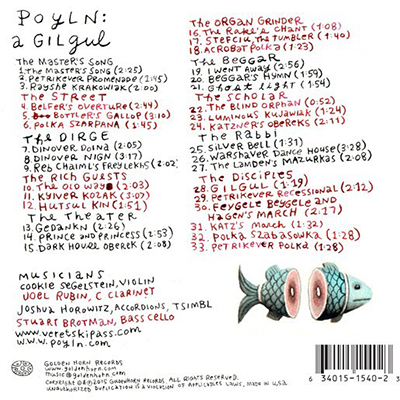

As ACTA continues with its initiative to explore the Sounds of California which we began earlier this year with partners, The Smithsonian Folklife and Heritage Center, Radio Bilingue, and the Library of Congress, the steady work of Veretski Pass demnstrates how music can reflect the immigrant story well. The Berkeley-based music trio (with guest artist, Joel Rubin, another luminary of klezmer,) received a Living Cultures Grants this year to support the production and California public performances of their new work, Poyln: A Gilgul. This recording represents the meeting of Jewish and Polish music which has been a missing link in the klezmer revival and repertoire. Due to the extermination of 6 million Jews in the Holocaust, 3 million of which were from Poland, the largest Jewish community in the region is notably subdued from the repertoire. In a markedly odd turn of events, today Poland is the scene of an almost raucous revival for all things klezmer. Largely taking their cues from the many American Jewish musicians who helped fuel the revival and add to the repertoire since the 1970s, it is not uncommon to see thousands of young Poles dancing to the infectious music of Jewish klezmer groups at summer festivals.

With the milestone CD release this year of Poyln: A Gilgul, (meaning “Poland, a metamorphoses”) the master musicians, have re-imagined, re-composed and re-arranged old urban and rural music to enrich the genre currently known as klezmer music.

The following conversation is adapted from both the Poyln website as well as from correspondence with Cookie as she travelled from a busy summer abroad performing and teaching.

***

LK: You all have classical training. What led to klezmer?

CS: Well, both of my parents are from Eastern Europe, my mother from Munkacs, and my father from Veretski. My mother is a survivor of Auschwitz and my father escaped from a Nazi labor camp. When they came to America they ended up in Kansas City, and ever since I remember I was forced to play and sing Jewish music for my relatives, which I hated! But, with the birth of my children, everything changed, and the tradition began to take on a new meaning for me.

LK: You have been significant in the revival of klezmer since the 1970s. When you reflect on where you are today and what it was like in the early days, what kind of catalyst was in place back then to breathe life into a near extinct musical genre and bring it back to life?

CS: For me it was a personal development. It wasn’t a situation where I saw a genre of music making a comeback, and wanted to jump on the bandwagon. Instead, it was a result of seeing how the culture of my parents was destroyed and watching them hold on to customs that I thought were backwards as a child. But when I was old enough to understand, I began to see their worth. Ironically, though, when I first started actually playing klezmer music professionally, my dad said, “Oy, vat is dat noise? Why would you want to play music that comes from that world? You should be playing Mozart and Beethoven!”

LK: Why the Poyln project?

CS: Well, as you may know, klezmer music has come to mean many things. But even if we can all agree that it’s the instrumental music of the East European Jews (which is how we’ve always defined it, put simply), this doesn’t take into account the galactic number of styles that exist in what we call “East Europe.” The majority of 78 recordings that exist of klezmer music come from what was formerly Bessarabia (today Moldova and Romania) and West Ukraine. When the so-called “revival” began in the 1970s, the repertoire was exactly that – Jewish music of that region, which came with all its typical stylistic characteristics, its collection of tunes. Poland was almost completely left out of the picture, despite the fact that there were some 3 million Jews living in Poland before the Holocaust.

LK: Why was Poland so absent from the repertoire?

CS: The popular Yiddish song, “Rumania, Rumania” tells almost everything we need to know. Romania was the symbol of cosmopolitan Jewish life. It was romanticized in a “wine, women and song” way. Even Ottoman Sultans requested that their court musicians include urban Romanian dances in their repertoire. And the Yiddish theater, which began in Iasi, Romania in the 1870s, became the standard of worldly entertainment. So once East European life got transplanted to America, the musical tastes of Romanian city life narrowed the style palette. If you look at the earliest klezmer fake book (a compilaiton of song leadsheets that have melody and chord changes) we have from 1916, The International Hebrew Wedding Music (reissued as The Ultimate Klezmer by Tara Publications, edited and arranged by Joshua Horowitz), there are at least 20 tunes of the 270 dedicated to Polish music, almost 10 percent – not a majority, but large enough to warrant attention, even in the klezmer revival; the tunes just don’t sound quite as “exotic” as the Romanian fare.

LK: What is it like to play in Poland now?

CS: The best way I can describe it is that it is a bizarre situation, which is not unusual, seeing as it comes from a bizarre history. Poland for me represents the most blatant incarnation of what is now called “Holocaust Tourism.” There are bands all over playing their versions of Jewish music, sometimes informed and sometimes conjectural. But the hunger for the ghost of Jewish past is palpable there. Szeroka Street is as close to a Potemkin Village as we’ll find – they are Jewish storefronts that are recreated to imitate what they looked like before the Holocaust, but not intended to function at all – they’re there just to look at. It’s the visual counterpart of the Polish klezmer revival.

LK: Who, besides the American Jewish klezmer groups, are playing klezmer music?

CS: It’s become a worldwide phenomenon. We just returned from Weimar, where we had students from all over the world, including Japan. But the centers for klezmer music now are still probably the U.S. and Germany, I would say. And the dynamics of the Polish klezmer revival are very different, from, say, the dynamics of Germany or the U.S.

LK: Are they playing Polish-Jewish, or Jewish-Polish music?

CS: Very little of either. They took the lead from the American revivalists and assumed the Moldovan repertoire that everyone else was playing. But just recently, a few Polish revival groups delved into the repertoire that has been deemed Jewish.

LK: What do we know about rural Jewish music?

CS: Great question. Not much at all, as the 78rpm recordings we have are commercial releases, and not field recordings. In other words, they’re not done in situ, or on site, so Jewish village music is practically unknown as it is barely documented. If we go by the attitudes of the professional klezmorim based on descriptions and manuscripts, we see that the repertoires were determined by the tastes of the clients. As those clients included non-Jewish communities, we could safely assume that they did indeed play rural music when they served those audiences. It’s interesting that rural musical phrases are embedded in the tunes that Moishe Beregovski (Ukrainian, Jewish musicologist in the Stalinist period) collected; even full songs.

LK: How do you know what is rural and what is urban?

CS: Well, there are some typical traits. One is the form itself. The simpler structures often show a simpler origin. Most folk dances are in two parts, AABB. Also, there are typical ways that folk tunes use the motifs of those parts. For instance, often you find the cadence (end phrase) of the first part forming the first phrase of the second part. Or a very repetitive phrase that goes round and round with little variations usually shows a more village-like origin. Harmonies tend to be quite basic and harsh dissonances are not eschewed. The upper class doesn’t tolerate such roughness as much in general I guess.

LK: So is the Poyln CD rural?

CS: It’s both. We’ve included the whole gamut of “classes,” from the very cosmopolitan ballroom stuff to the earthy, repetitive trance-like stuff, as well as Hasidic court music, and even the Kolberg tunes. He was Poland’s pioneering folklorist, who lived from 1814-1890. He was actually a Catholic monk who was an avid collector, and did publish some Jewish tunes in his 33-volume work, mostly from Mazowia. Since the transcriptions he made were simple and schematic, we’re pretty much on our own as to how to play them, so we simply played them the way we do other co-territorial music, with a Jewish musical “accent.”

LK: You are based in Berkeley, California. Can you say anything about the California impact on Veretski Pass? Is there a California connection to your work?

CS: We’re very connected to the Bay Area. Just the fact that we now, all three, live within a mile of each other, means we can develop projects face to face. You can’t take that for granted. Josh’s European band, Budowitz, has members from Hungary and Germany, and Stu’s other band, Brave Old World, is scattered between Scotland, Germany and Chicago, so rehearsal for them is a luxury and program development can be really arduous. The Bay Area has become so important to us, because we are called on to play every community function imaginable. People often think that international touring bands only play on the stage, but our bread and butter is the community, and we’re very integrated here.

LK: It is almost the Jewish New Year, is there anything from the repertoire you would like to share with the readers for a sweet beginning?

CS: There are many melodies set to the Hebrew prayer, Avinu Malkeinu (Our Father, Our King), and this would be the text that most people know:

Our father, our king

Inscribe us, seal us

In the good book of life

***

Enjoy “The Lamden’s Mazurkas” from Veretski Pass with Joel Rubin:

CD information here: http://www.poyln.com/Poyln/CD.html

For a calendar of upcoming Veretski Pass public performances check here: http://www.veretskipass.com/veretskipass.com/Schedule.html