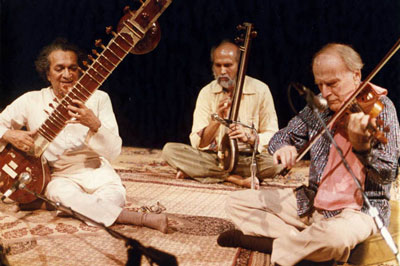

Editor’s Note: This month, ACTA acknowledges the recent passing of two musical giants of Indian classic music who died within a month of one another. Ravi Shankar and Harihar Rao were friends for over 60 years. The master of sitar is almost synonymous with the words “Indian music.” His protégé Harihar Rao began his studies with Maestro Shankar in 1946 and they would together found in 1973 a preeminent organization dedicated to the presenting, producing, and perpetuation of classical Indian music; the Music Circle (two-time Living Culture Grants Program grantee) is located in Pasadena, California.

We invited David Roche, one of ACTA’s co-founders and a life-long student of Indian traditional music, to reflect on the California context of Ravi Shankar’s life and impact.

It was Dick Clark, the “world’s oldest teenager,” media impresario, and host of American Bandstand for thirty years, who famously said, “Music is the soundtrack of your life.”

It was Dick Clark, the “world’s oldest teenager,” media impresario, and host of American Bandstand for thirty years, who famously said, “Music is the soundtrack of your life.”

It was his afternoon television show in the late 1950s and 60s that introduced Baby Boomers like me to the worlds of Elvis and Motown, Chubby Checker, Ike and Tina Turner, Sam Cooke, Buddy Holly, Aretha Franklin, and just about every other troubadour coming out of the increasingly gritty Rust Belt or deep South to join a swelling pantheon of sonic revolutionaries.

His thoroughly integrated Philadelphia TV-studio audience, jerking and twisting to up-to-the-minute dance moves, and his lineup of black and white stars broadcast an unstoppable wave of change for upwards of twenty million teen viewers per afternoon by 1959. Clark was the youthful face of a thoroughly subversive pop music culture that our parents ridiculed. So long Mouseketeers. Say hello to sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll.

Dick Clark died last April at age 83, in the same year that the “Godfather of world music,” Ravi Shankar, died at age 92. In my mind, there’s more than a hint of cosmic musical mashup that is suggested by this synchronicity — the idea of an arc of late 20th-century music culminating in a harmonic convergence reaching its apogee at Monterey Pop in 1967, or, more significantly, at the most iconic rock festival of all time, Woodstock, in 1969. Through those events, Ravi Shankar and his avuncular tabla partner, Alla Rakha, became larger-than-life figures indelibly embedded in the Boomer ethos. Those two otherworldly musicians were brothers from another planet we could trust, even if they were over thirty.

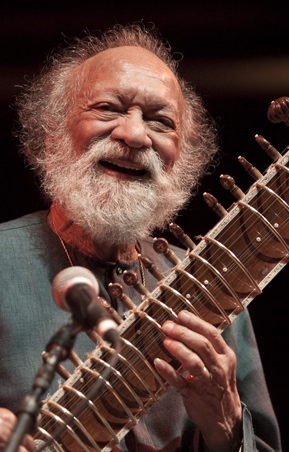

The late Ravi Shankar’s astonishing reception in the West and his ability to surf the zeitgeist of American pop culture for decades speaks volumes about the genius of a consummate international showman who also possessed a supremely fertile musical mind.

In a sense, Ravi Shankar, beyond the borders of India, was following in the footsteps of such 19th- and 20th-century fellow Bengali gurus as Swami Vivekananda and Paramahansa Yogananda (Autobiography of a Yogi) and in the wake of his brother Uday’s successful “Hindu Ballet” tours with impresario Sol Hurok’s “S. Hurok Presents” productions beginning in the 1930s, productions in which Ravi himself began his journey to the West as a teen solo dancer.

The profound effect Ravi Shankar has had on the way we hear all music today is a unique legacy for the entirety of Indian music, comparable to the way we hear all blues because of Robert Johnson or all jazz because of Charlie Parker and John Coltrane or all Bach because of Glenn Gould. Ravi Shankar’s music has literally grooved our ears.

The profound effect Ravi Shankar has had on the way we hear all music today is a unique legacy for the entirety of Indian music, comparable to the way we hear all blues because of Robert Johnson or all jazz because of Charlie Parker and John Coltrane or all Bach because of Glenn Gould. Ravi Shankar’s music has literally grooved our ears.

For a young and impressionable American musician growing up in the 1960’s, Ravi Shankar’s music was a touchstone. His music had both the emotional appeal of rock and the intellectual integrity and exploratory freedom of thoughtful jazz.

I remember an early duet LP recording with Ravi on sitar and Ali Akbar Khan on sarod and the exquisite raga modal polyphony they generated in Palash Kafi and Bilashkhani Todi. This recording, eventually worn out by hundreds of replays, was a sonic tipping point for me. Though I didn’t have the words for it at the time, I was hearing and experiencing a soundscape of the deepest jazz built on thousand-year old charts and an expression of an Indian emotional world that lay somewhere just beyond the horizon. I ended up chasing that rainbow of gorgeous improvised music to India and back several times over the years, swinging as if suspended between two planets.

On my first visit, I was fortunate to make friends at Banaras Hindu University Music College with Ravi’s nephew, the sitarist Ananda Shankar, and spent wonderful days at the Tollygunge-district Shankar family flat in Kolkata where he and his parents, Uday and Amala Shankar and sister, Mamata, had their headquarters. I was swept up into the heady curry of Bengali music, theatre, writing, politics, dance and film of the late 1960s, in a salon-like atmosphere featuring regular musical soirees and critique of the world over chai, as viewed through a Kolkata lens.

I arrived back in San Francisco in 1967 a month after Ravi and Alla Rakha had ravished the audience at Monterey Pop. While Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were holding psychedelic court at the Fillmore, Ravi was connecting in London and Los Angeles with George Harrison. Pop music, jazz (Coltrane was an acolyte), new music (Philip Glass in Paris), world music at university ethnomusicology programs (Ravi on the faculty at Cal Arts), hippies, and weed were all literally up in the air. It seemed like music was going to be forever transformed into a heady mind-meld of modes and improvisation, a new musical world without discernible borders.

Many of us Boomers latched deeply onto something beautiful and positive from this expressive interpretation of ancient Indian culture in music. It had arrived in our time and space as an antidote to the horrible headlong dive into Vietnamese War madness and the vortex of hopeless militaristic negativity and unnecessary suffering throttling our world. Hindu and Buddhist missionary gurus arrived in numbers and built flocks of followers. Ravi’s religion was music and as much as he eschewed hippy excess and ignorance and struck a superior pose at times, he too had a faithful flock.

It was this flock, nurtured through his loving association with George Harrison, that rose to meet the occasion of a political tragedy in South Asia and, in two packed performances, sold-out the seminal benefit concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden in New York on August 1, 1971, leading to what became the first of several Grammy-winning recordings. The “Concert for Bangladesh” represented an early example of how music performance could simultaneously generate new charitable giving and greater social awareness, a theme that was to influence other socially-engaged musicians and promoters who followed as they began to realize the enormous consciousness-raising command a pop music event could have in educating mass audiences and “marketing” social activism.

For many first-generation immigrant Indians to California arriving post-1960s, even those steeped in all things Western, Ravi Shankar was the premier living legend of South Asian cultural genius, a performer able to bridge the gap between the high-profile rock and classical worlds of the Beatles’ George Harrison and violinist Yehudi Menuhin on the one hand, and the worlds of traditionally conservative Hindustani classical musicians and Satyajit Ray and the Bengali arts intelligentsia on the other.

Sandip Roy, in his charming remembrance of Ravi for New American Media (12/12/12), went so far as to call him “our Columbus,” the man who landed on these shores and firmly planted a flag for musical diversity, opening the way for all Indian musicians who followed, north and south, Hindustani and Carnatic.

Eventually, the Maihar gharana (lineage) style of Hindustani music that he and Ali Akbar Khan brought to California in the 1960’s subdivided and relocated itself organically with Khan in the north in San Rafael with the Ali Akbar College of Music, and Ravi Shankar in the south with the Music Circle he founded in 1973 with the late Harihar Rao in Pasadena at Claremont College and with private sessions he provided at his home in Encinitas. Both the College and the Music Circle continue to serve audiences and students magnetically drawn to the world of Indian music and remain an enduring legacy of these two musical giants.

Eventually, the Maihar gharana (lineage) style of Hindustani music that he and Ali Akbar Khan brought to California in the 1960’s subdivided and relocated itself organically with Khan in the north in San Rafael with the Ali Akbar College of Music, and Ravi Shankar in the south with the Music Circle he founded in 1973 with the late Harihar Rao in Pasadena at Claremont College and with private sessions he provided at his home in Encinitas. Both the College and the Music Circle continue to serve audiences and students magnetically drawn to the world of Indian music and remain an enduring legacy of these two musical giants.

Roy wrote, in comparing Ravi to Columbus, that, “While one explorer came looking for India, the other took India to the world.” And in that process, a stellar hybrid music was created. As an anonymous commentator for the New Yorker wrote on Ravi’s death in December, Ravi established a “real standard of musical genius: total individual commitment, dedication, and mastery joined with a collaborative generosity and a beginner’s open mind.”

Menuhin, whose admiration for Ravi’s musicianship knew no bounds, summed up Ravi’s contribution in eloquent terms in a forward to the autobiography, Raga Mala:

“Ravi represents enlightenment, organization, discipline – and yet such freedom. Freedom that is won through a great deal of thought, work, practice and experience…. In many ways, he is the greatest musician I have known.”

It is these enduring contrasts of discipline and improvisatory freedom that remain the hallmarks not only of Ravi’s life and career, but also of the genres of Indian performing arts for which he was a leading representative. Yes, the sitar became a Western craze in 1965 with the Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood,” the Kinks’ “See My Friends,” and the Rolling Stones’ “Paint It Black.” But the deeper music, unlocked at times in a Ravi Shankar alap (free rhythm improvisation) or evoked in the score for Ray’s Pather Panchali or Attenborough’s Gandhi, revealed the genius within and the command of media modes that made Ravi Shankar such an unforgettable musician for our times and a major composer of the soundtrack of our lives.

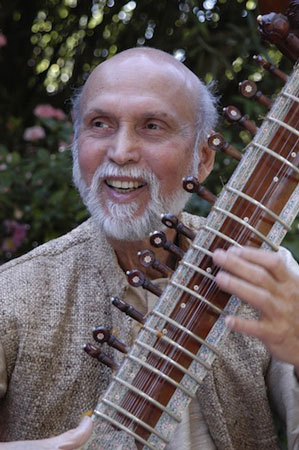

In another music learning period for me in India, I lived in Tilbhandeshwar alley in Varanasi, around the corner from where Ravi Shankar was born in 1920. At his 50th birthday concert in Varanasi in 1970, I met him backstage and told him that I had been born there in Varanasi as well – at the age 20. He flashed that wonderfully elfin smile of his and laughed heartily. Yes, he could relate to invented reincarnation.

And so I bid a fond farewell to Ravi Shankar in this lifetime, silently hearing a ubiquitous Varanasi mantra playing in my ear: Rama nama satya hai (“God’s name is Truth” – a funeral dirge heard day and night in processions leading to the burning ghats in this holiest of Hindu cities).

Dear Ravi. Thank you. Your music was such a revelation.

David Roche is an ethnomusicologist and Governor for the San Francisco chapter of the Recording Academy who nominated Ravi Shankar for the Lifetime Achievement Grammy that he was awarded posthumously in February 2013.