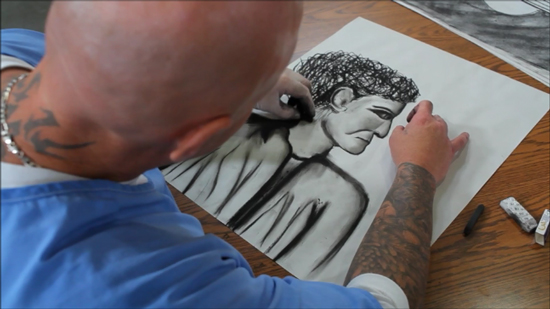

After a few weeks of inconsistent attendance, with new students appearing every week while others not showing up, and not having accounted for the pace of how things move at Corcoran, I began wondering if I was going to get through the first art assignment by the end of the thirteen weeks. For their first assignment, I wanted to evaluate their capacity of manipulating dry-drawing materials, their technique, and their understanding of tasks. My expectation was that students would be able to complete a scale drawing from a photo resource within a few classes. In spite of these challenges, the work was great. The students had a firm grasp of the dry-drawing materials of pencil, eraser, and home-made cotillions. The work began to take shape. The work demonstrated the ability to utilize line, scale, value, and materials. Many of the students’ drawings were delicate, precise, and visually commanding. We began to have weekly conversations about how personal experiences both in and out of incarceration can be a launch pad for their drawing content and how art can expand the boundaries of understanding one’s own pain and build resilience.

After a few weeks of inconsistent attendance, with new students appearing every week while others not showing up, and not having accounted for the pace of how things move at Corcoran, I began wondering if I was going to get through the first art assignment by the end of the thirteen weeks. For their first assignment, I wanted to evaluate their capacity of manipulating dry-drawing materials, their technique, and their understanding of tasks. My expectation was that students would be able to complete a scale drawing from a photo resource within a few classes. In spite of these challenges, the work was great. The students had a firm grasp of the dry-drawing materials of pencil, eraser, and home-made cotillions. The work began to take shape. The work demonstrated the ability to utilize line, scale, value, and materials. Many of the students’ drawings were delicate, precise, and visually commanding. We began to have weekly conversations about how personal experiences both in and out of incarceration can be a launch pad for their drawing content and how art can expand the boundaries of understanding one’s own pain and build resilience.

One of my students told me a story about when, how, and why he began to draw. In prison, all he had for artistic inspiration was a copy of book of cartoons entitled Calvin and Hobbs, so he began to copy illustrations from it. He said he never thought about art as a child, but once he was locked up, he turned to it. After listening to his story and others like his, I realized how art helps keep you sane. It provides structure to days that never end.

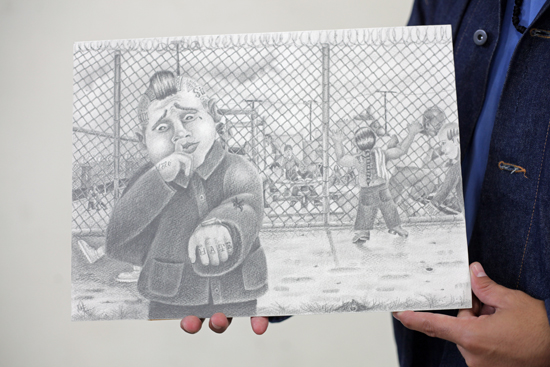

“What do you want to know?,” was a question that an inmate asked me six weeks into the program. I told him I did not need to know why he was here, but I did want to understand what he wanted to learn in this class. His answer was simple: he wanted to be part of something, to talk with others about art, and to create art with others. He wanted a hobby card. A hobby card grants inmates the ability to have art supplies in their possession and not have them confiscated at any moment. But it was still heartbreaking to witness the power dynamics in prison, even for artists. My students told me that it is difficult for them to keep artist materials and their artwork in their “homes” (they used the word “home”). At times their works are destroyed, removed, and confiscated without warning or without reason. In many cases, these works of art are the results of hours, days, weeks, months, and years of time. Time is a construct that is taken out of the equation when creating certain works of art. Art is used as a commodity to be traded and sold within the yard, with the CO’s, and in society. To use art as a tool to change or add to the existence of humanity is rare.

Adjacent to the dining area there is a small room where the door is always closed. One time, we happened to pass by to meet with an employee in their office and saw that the door was cracked open just enough to see a group of inmates sitting on a short bench while the CO’s perched above read Guns and Ammo, Surfer, People, and US magazines while having their black boots shined by Latino and Black inmates dressed in white jumpsuits with the institutional acronym in black. While we understood that inmates had job duties that included cleaning, it dawned on me that shoe shining might be included in this, but it was still a shock to me. It was at that moment that it sunk in to me. The scene was too familiar, reaching my subconscious mind, one that I had read about as a college student. The role of prisoner and guard is clearly defined and extends outward unto every facet of the correctional facility.

At our first training in Norco (a corrections facility in the City of Norco), I was presented with information that told me that I would be compromised and manipulated by an inmate. A book titled The Anatomy of a Set-Up was given to us and explained in a-matter-of-fact tone that inmates are ruthless and will stop at nothing to manipulate me. Repeatedly, I felt that I was singled out as weak and impressionable, traits that common folks, and especially artists, exhibit. We were warned that we might fall victim to the evil plans of the master criminals present in each of our classes and that the guards are our only protection and the only people that can be trusted within these walls.

But I don’t feel any alliance with the guards. Every time I cross through the prison entry gate and exchange my California driver’s license for a corrections identification card, the fear instilled by years of institutional conditioning sets in. A sense of holding my breath overcomes my body until the moment I exit the last gate, the guards peer into my automobile filled with artists’ supplies, check me out, return my CA driver’s license and give the okay. Every week, a sense of oppression sets in, a fear that the guards will find something wrong and detain me. My identity will be lost in the system and I will spend an undisclosed amount of time in prison for being an artist.

My experience as an instructor has flipped the notions of what is considered normal and abnormal. All of this is normal, to operate without compassion, to exist as a human in a social environment without regard to the emotional well being of others. It is without saying that there are employees of the warden of a prison that check their compassion at the gate before entering. At the end of it, I am an artist who has worked in particular communities building relationships with people who have been marginalized by a system designed to create inequity. I cannot help but see the negative impact that prison has on humanity and I can also see how these courses help foster community by sharing and creating in a shared art space.